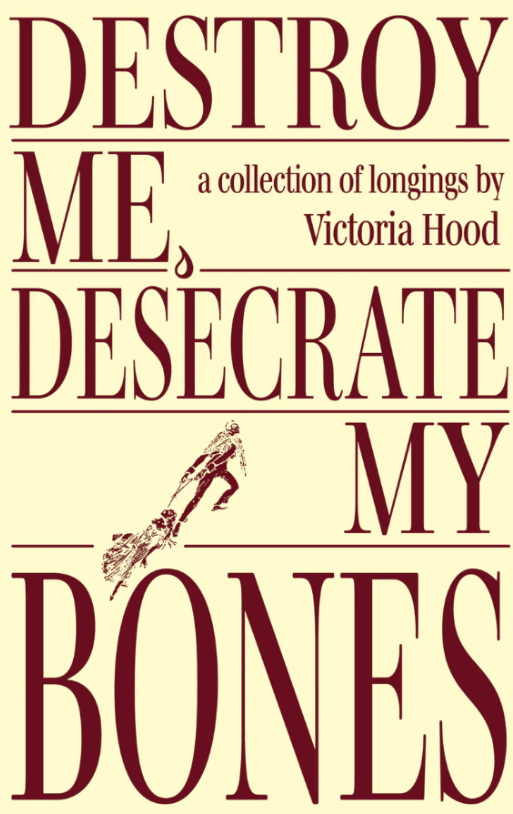

Book Review: Destroy Me, Desecrate My Bones: A Collection of Longings by Victoria Hood

Destroy Me, Desecrate My Bones is available here.

In her new book, Destroy Me, Desecrate My Bones (Girl Noise Press, released February 10th, 2026), Victoria Hood greets us with a series of bizarre questions, including “How many skeletons are in your closet?” and “Do you want to drip?” and “Are you collecting your loves?” and “Have we reached the bottom yet?” (11). These are the questions with which we grapple in Hood’s experimental meandering of queer love, desire, and identity. Organized into six sections — “To Contain,” “To Devour,” “To Mend,” “To Become,” “To Tend To,” and “To Spill Over” — the “collection of longings” invites readers to consume, digest, and consume again an innovative assortment of stories, poems, essays, and charts. This unapologetic voyage into the strange, surreal, sensual, and sticky will appeal to fans of other experimental writers like Sabrina Orah Mark, Maggie Nelson, Renee Gladman, and Franny Choi.

As a queer woman, some of Hood’s stories get under my skin. Others feel like they are my skin. And oh, how good it is! Hood pries at the layers of my queer identity, opening me up to whisper secrets into my flesh before stitching me closed again and sealing it with a kiss. I have been reading Hood’s work for years, and each of her books offers permission for queerness, grief, and vulnerability to exist loudly on the page. As a writer myself, Hood’s stories motivate me to get back to the page and get weird. Her work asks us to shake off those stifling canonical constraints and embrace the creative urge to not give a fuck.

Destroy Me, Desecrate My Bones is a book concerned with cohabitation—not only in the house, but in the body. She interrogates the boundaries between self and structure. In the opening poem, “The House,” the house says, “I am aching / I am aching” (15). The speaker responds, “I know that these words are for me, I live alone, I am unattended / in a home that is in love for me, in a home that is my protector, / in a home that is learning how to speak to me” (15). The poem evokes key questions that resurface throughout the collection: within what am I contained? and what do I contain? The book reveals two disorienting and essential truths: that our bodies are the homes where our yearning, fear, and pain lives; and that the spaces we inhabit also inhabit us.

Jumping from wit and sarcasm to gut-wrenching strokes of devastation, the collection traces experiences of girl- and womanhood through honest, occasionally brutal portrayals of sexuality, love, grief, and growth. In “Application for Cohabitation Form P-M-94X,” Hood constructs a complex, wholly realized alternate universe in which it is prohibited by law for two poets to live in the same domicile. What results is an uncanny exchange between a poet, their musician-partner (who insists they are not a poet), and the government official seeking to enforce the rule. The dialogue-only story gestures toward metanarrative, leading us to wonder: within the “house” of this book, what belongs? If you think essays, fiction, poetry, and graphics cannot cohabitate peacefully within the same collection, Hood’s latest book proves you wrong.

Hood is known for her playful, rhythmic prose, and Destroy Me, Desecrate My Bones is no exception. Take, for example, this excerpt from “Baby Girl”: “My baby girl is all snuggles. All snuggle snuggles and no grief. My baby girl has never talked back…” (69). And this moment from “Girl-Y”: “You are my friend I’d like to fuck. My FILF, my FILTH, my FILTHY little friend that I’d like to see what you can do” (52). Hood’s sentences immerse themselves in sensory stimulation; her words drip and stick and tear and smear: language is sentient.

With “A Series of Diagrams: Ranking Tactics of Childhood Bullies,” Hood pushes the text’s playfulness beyond the linguistic and into the visual. The piece contains the familiar repetition so characteristic of Hood’s style, only this time it is rendered with lines and shapes. What happens to the words that wound us when we shape and re-shape them into charts, figures, and symbols? Perhaps these diagrams embody the ways in which we compulsively live and re-live our traumas, forming and re-forming them to fit into our ever-changing bodies. And yet, at the same time, restraining painful memories within discrete borders and labels revokes their power; it organizes the chaos into meanings we can hold, dissect, and—ultimately—destroy.

Experiences of multiplicity—of identity, of form, of self—extend to Hood’s portrayal of polyamory throughout the book. Positioned near the collection’s end, “Bolides” immerses us in a world so swollen with queer love that one feels it ooze from the page. “My body will not stop creating and secreting more and more love for you both,” Hood writes. “My house reeks with the smell of love” (166). In a moment when queer identities and relationships are being subjected to relentless persecution and systemic violence, Hood crafts representations of attraction and devotion so simple in content yet limitless in capacity. In “Debris Desire,” the narrator remarks on such multiplicity: “I knew the whole time that my love does not end, it is a well with no bottom, I can put all of me into more than one” (167).

As readers of So to Speak, it’s safe to assume that we share a love for writers who challenge the very stale, very male literary canon. We are starved for books that resist the pervasive systems of marginalization and dehumanization, and we share an appetite for stories that remind us why we fight for freedom. Hood’s book is a six-course meal that both satiates and inspires us to cook up our own riotous recipes. With a delicious balance of feminist wit and rage, Hood exposes the inherent absurdity of our heterocapitalist society. In “I’m Sorry We’re Getting Married,” the narrator grapples with their decision to participate in an institution so rooted in ownership and control over women’s bodies:

I love you, Harry. [...] But then there is the question of insurance in a country that doesn’t care if you live unless you’ve decided to marry someone who can help you. I love you, Harry. And I’m wondering if it's insurance fraud to marry even if you don’t believe in the institution of marriage. But you are a bartender and someone needs to bring home the healthcare. (33)

In a collection steeped in love, sex, and queer joy, moments like these remind us that our society is designed for an elite minority. Sure, sometimes we have no choice but to fall in line—but in the meantime, we carve out corners of resistance. We construct communities rooted in tenderness and compassion. Hood’s book is a tribute to the communities that sustain us: “If time is cyclical, if I have to keep living this timeline again and again: I couldn’t imagine it without either of you, I don’t think I could untie my boat from your dock” (“Debris Desire” 167). The book is a reminder that we are not lost at sea. We can build bridges between our docks.

To my fellow queer readers, feminist readers, sad-girl readers, and freaky readers: Hood’s collection contains you. It contains us. Like the narrator of “Closet,” we “crave softness” in a world that is so hard (17). Hood’s collection is a place to rest our misery; a venue for the wreckage and a space to honor the absurd. The book insists on our right to grieve, not only for what we’ve lost, but also for what we’ve carried—often without even knowing how heavy it was: “Until I actually lost you, I didn’t realize I needed to” (“Hopeless” 21). In Destroy Me, Desecrate My Bones, there is room for the whole mess: sorrow and joy, despair and hope, hatred and humor.

Yes, this book contains multitudes. Actually, it fails to contain. It spills over, it makes a mess, it takes up space and leaves a mark. And Victoria Hood is not interested in cleaning it up. “I’ve never been delicate,” says the narrator of “Girl-Y.” “I’ve never understood how softness works” (112).

So, have we reached the bottom yet? According to Victoria Hood, when it comes to our capacity for love, the bottom is just an illusion.

Victoria Hood has previously published two collections: I Am My Mother’s Disappointments (Girl Noise Press, 2024) and My Haunted Home (FC2’s Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize Winner, 2021). She has also released two chapbooks with Bottlecap Press: Entries of Boredom and Fear (2023) and Death and Darlings (2022). Destroy Me, Desecrate My Bones was published by Girl Noise Press on February 10th, 2026 and can be purchased here.

Michelle Hoeckel-Neal (she/her) is a queer writer, teacher, and PhD student living and working in Fredericton, New Brunswick, where she writes short fiction and poetry. She earned her Master’s in Creative Writing from the University of Maine. Her words have appeared in New Session, JAKE Magazine, Every Day Fiction, and others. You can find her on Bluesky @MHN-hello or at sites.google.com/view/michellehoeckelneal.