Writing the In-Between: A Conversation with Maggie Stiefvater, Author of The Listeners

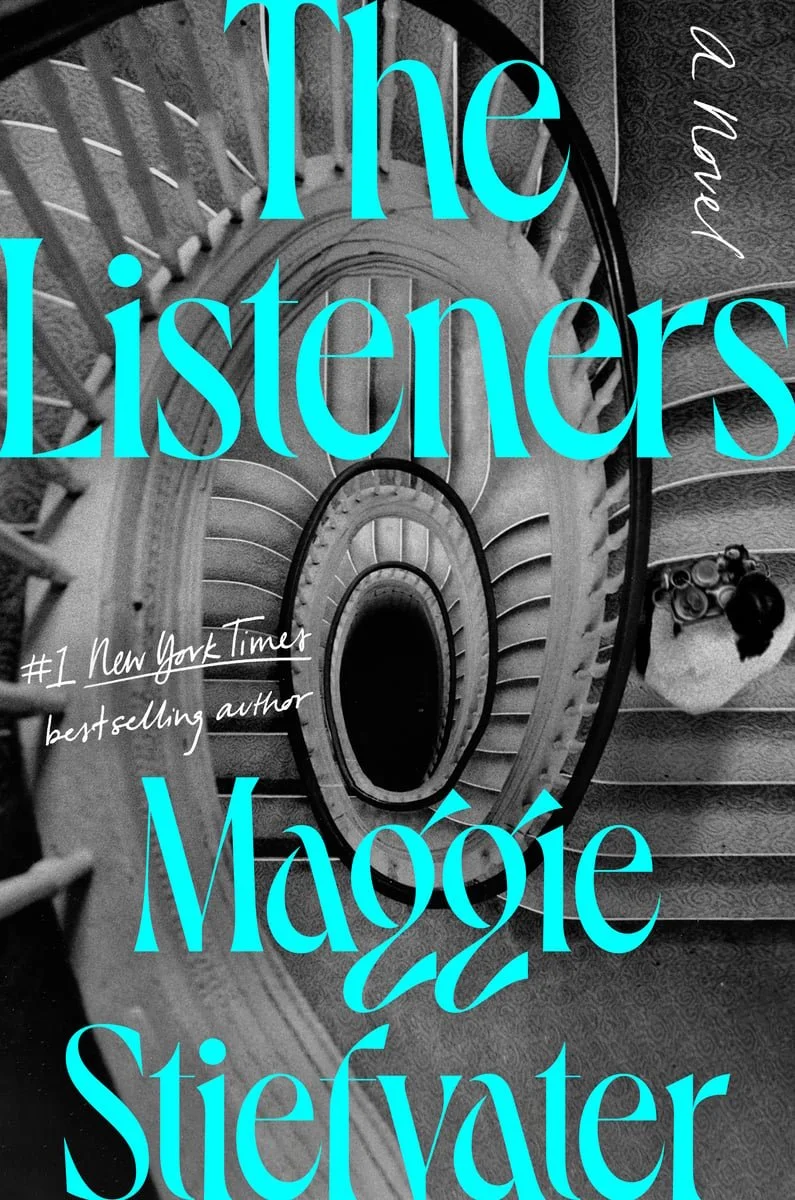

Maggie Stiefvater is the author of 20 young adult and middle grade novels, including Shiver and The Raven Cycle. Her adult debut, The Listeners, follows a West Virginia luxury hotel manager and the Axis diplomats she’s forced to host, all while the hot spring below the hotel grows restless. The Listeners was published on June 3rd, 2025 by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

In connection with Fall for the Book 2025, Maggie spoke with So to Speak about portraying neurodivergence, constructing identity, and living in the in-between spaces.

You can purchase The Listeners here.

Photograph of Maggie Stiefvater.

Shay McIntosh: Much of your writing features a working-class character who enters the world of the rich. Similarly, your female protagonists often exist in male-dominated social spheres. What interests you about that dynamic?

Maggie Stiefvater: When I was in college, I was a competition bagpiper. There was one other lady piper in the entire state of Virginia. My entire college experience was being surrounded by men. Then I got into car racing, which is, again, a very dudely place. And I grew up to be the breadwinner of the family. I am a wife and a mother, but I was also the person who was putting the dinner on the table while my husband raised the kids. Looking at the ways people still respond to gender, I just know I’m gonna be working on that forever.

After college, I was a full-time portrait artist. Who pays for portraits, right? So you're getting into your shitbox and you're driving to an estate where someone is paying you to paint their stallion, or their child, or their child and their stallion. And who can afford me is someone that I could never afford to sit next to. As an artist, you move in all of these spaces and you become fluent in them, but you are never part of them.

I really wanted to write a book that was about being in those in-between places that wasn't about someone learning that they had to find themselves in a different space. Like, instead, to learn the fact that in-between is a space of its own and you could stay there forever.

SM: I noticed The Listeners capitalizes both White and Black in June’s narration. What is your philosophy towards writing identities that would have been seen very differently in your book’s historical setting than they are today?

MS: When you're writing a novel, there are two points of view that you're thinking about. Your characters are experiencing one story, but your reader is experiencing another. Capitalizing “White” and “Black” is the story for the reader. It's not being said in June’s dialogue. She's not being asked to say something anachronistic. Instead, when she is actually thinking, she is thinking about what it means to exist in West Virginia at that time. It's unusual for her to be a woman who is managing a hotel. It's unusual for Griff, her chief of staff, to have gotten as high as he could, but she also knows he's topped out because he’s Black. They have no status outside of the hotel, and she understands this. The hotel has its own stratosphere that it exists in.

She gets to think all these things because she would know them in that time, which I know because I was reading all of these hotelier memoirs of the time. I tried to do my best to make sure that it's a modern story about people who are not thinking in modern ways. She's cool, but I think she's cool in a way that many people were at that time.

SM: Neurodivergence is a flashpoint in our political discourse right now, often in incredibly damaging and dehumanizing ways. How did you approach writing a nonspeaking character, Hannelore, whose internal experience is so different from how the world perceives her?

MS: It was wild to watch this become an even bigger item after this novel came out, when I just thought I was gonna write about the people around me. I really love the statistic that 50% of OCD kids never get a diagnosis because their parents think that they're normal. I have OCD and one of my children has OCD. I just think, oh, that’s a way of processing the world, and then people go, what the fuck? And I’m like, right, sure, okay, I understand that you have an ICD-9 code for that.

I was inspired to write this because of a very real moment with the diplomats that I read about. The German attaché’s son, who was 16, had just been diagnosed with schizophrenia. He knew that if his son was repatriated with him, the country that he represented would probably kill his son. So he made an under-the-table deal with the State Department to have his son stay here and never see him again. I was so fascinated by this, particularly because it turned out that was not the correct diagnosis; the son went and had a life out as a farmer in the Midwest. He never saw his family again.

I wanted to do that story justice with Hannelore. I also wanted to do justice with the story of June, who is also neurodivergent, to show how you could still achieve positions of great power within that. Not despite that, but because of it—not as a superpower, not like Monk, but instead, just, there are slices of ways of looking at the world, and this is another way that you have to come of age.

The thing that was actually most terrifying about this was: I write to my experience. I always steal characters, either myself or other people I know, and write the spaces between them. I was really asking a lot of the reader to say, I want you to see the commonality between Hannelore and June. It is a spectrum and there are shades all the way along. I'm asking you to just play in that space instead of labeling it, because labels can be—I mean, the whole book is about how labels can lump you all together in a very dangerous way.

SM: The attaché’s son was 16, but Hannelore is 10. I was talking to my children’s librarian friend, and she pointed out that some children's literature frameworks view children as a marginalized group in themselves…

MS: That is a very peak library/MFA question.

SM: …so this is your adult debut, but it features a child narrator. What factors played into your decision to make one of your perspective characters a child?

MS: I really wanted to play with the idea of responsibility in this book. The major responsibility that June feels is to her staff, who are looking to her: is it okay to be giving the enemy luxury? And she has already been telling them it's okay to give the wealthy luxury, despite the fact that the staff will never have that. She has trained them in this, and they believe her and trust her implicitly. So her sense of responsibility means that the real focus has to be a child. It has to be someone who is completely unable to make a decision for themselves.

SM: You said June has made her staff believe it is right to give luxury to these Axis diplomats. What do you think?

MS: Diplomatic reciprocity is what, I think, makes us American. The rules of war are supposed to be that diplomats cannot be imprisoned. They represent the ideals of the country that they belong to. To show that we are part of a civilized world, they are meant to keep those channels of conversation open. They are to be kept, not detained. [The U.S. government] requested that these luxury hotels keep their current standard. Americans in German hotels and Japanese camps were starved, and [the diplomats we hosted] were treated well. Many of them still wrote fondly about the experience later. To me, it's right because we were right. It doesn't matter if they were right. We were right.

SM: Were you thinking about the ways this story would and would not play into the national myth about the American experience of World War II?

MS: Yeah, absolutely. That is always the legend: once upon a time, there were the Nazis, who were the absolute bad guys, and then there was us, the absolute good guys. The Nazis did not exist in a vacuum, and we did not pay attention to those eugenics programs for a very long time because we were doing variations of them. Having the mention of Prager, the German who was lynched here in the US, felt very important to me, to show how every single country was coming of age in this toxic soup of nationalism and mob justice.

SM: You bring up eugenics specifically, which is the facet of Nazi ideology that is the major focus of this book. There is a more minor focus on Jews and antisemitism. How were you thinking about that?

MS: It was really interesting to be working so closely with the historians on this, because I'm not sure it makes for great fiction. One of the historians told me the reason there was very little antisemitism in the hotels is because there were no Jews there at the time. The waitstaff would have been all [non-Jewish] Germans and French, and the maids would have been entirely West Virginians. He said it was just a component that was weirdly missing, an echo chamber. If anything, I think I could have talked more about the lack of it.

SM: This book engages pretty directly with Appalachia’s history and image. What do you hope readers take from your portrayals of the region across your work?

MS: One of my sources for The Listeners was 18th-century letters about the hot springs. The fellow talked about a spring where the hot spring and the cold spring came out of the ground so close together that he could put his hand in each of them if he lay between them. You wouldn't, though, because it was covered with moss, and on top of that moss were hundreds of beautiful snails. And I remember thinking, first, I wanna go there, and then, immediately, No, because that would ruin it. That feels like the battle of this region forever.

SM: You have had, at this point, a pretty long and commercially successful career. How do you navigate that, and how does your personal identity play into it?

MS: I have had a phobia my entire life of repeating myself. Every reader who has read the work of a very prolific writer at a certain level goes, oh my God, this is the same book. Doing that on purpose is one thing; going and writing the same story again and again by accident, like, Oh, that's just her relationship with her husband… Why am I here in this book again, watching them? That's so, so creepy. I just wanted to make sure that, with every single project, I'm always thinking, Am I saying something different? Why am I saying something different?

As far as identity… I was sitting in a shuttle coming back from giving a TED talk next to a really clever guy and he asked, “what do you think your superpower is? I looked you up and I see that you do writing and you do music and you do art. So what ties all those together?” And I remember telling him, “I think it’s probably storytelling,” and he went, “Nope.” You just met me, dude! He goes, “No, it's changing people's moods.”

SM: Do you think so?

MS: Yes. 100%. Because when you pick up a book, what's most important to me is how you feel when you're done with that book. When you go and hear me speak, you should be leaving punching the air, Woo, what a great time out. If you're listening to music, I pick the mood beforehand that I want you to be in.

SM: You've said a couple of times that you really care about intentionality, you don't want to do something accidentally. Do you think you have a fear of accidentally being known in a way that you don't want to be?

MS: When I was a kid, I was very Hannelore-like. It was like I was a space where a child was. I was such an observer. I feel like, in many ways, I don't exist in an external form. Everything that you have seen is a thing I have attached to myself to make it easier for you to understand a facet of my internal landscape. There's nothing like having someone interpret you incorrectly and going, I know that you're making assumptions about me based upon a people-system in your head, but you ain't met anyone like me.

Maggie Stiefvater writes books. Some of them are funny, ha-ha, and some of them are funny, strange. Several of them are #1 NYT Bestsellers. The Listeners, published by Viking, is available for purchase here.

Shay McIntosh writes about dyke drama. She has been published in the Rose Books Reader and Slate Magazine, and was a Writer-in-Residence at Sundress Academy for the Arts. She is a first-year MFA candidate in fiction at George Mason University.